Their History Within the Broader Historical Context and Through the Written Sources Referring to Gomfoi

Thessaly — the land of the mythical king of Phthia and progenitor of the Greeks, Deucalion, and his wife Pyrrha, whose ark, after Zeus’ deluge, is said to have come to rest atop Mount Karava in the Agrafa mountains. A land which Poseidon, the “earth-shaker,” transformed from sea into a fertile basin. A land of the Pelasgians, Minyans, Aeolians, Boeotians, and many other Hellenic tribes. On the western fringes of this territory, the ancient city of Gomfoi was founded — a sentinel city guarding the passes between Thessaly and Epirus, and for that reason, a frequent target of armies, generals, and kings of the ancient world. Among these were two of the most renowned: Philip II of Macedon and Gaius Julius Caesar.

According to current archaeological evidence, the city of Gomfoi was established in the 4th century BCE through the unification of smaller settlements (kōmai). However, the transition from organized Mycenaean settlements to the Thessalian cities of historical times remains a current topic in Thessalian archaeological research. A key point of inquiry is Homer’s description of Thessalian settlement patterns in the Catalogue of Ships, as preserved in Book II of the Iliad:

“Those who held Tricca and rocky Ithome, and those who held Oechalia, the city of Eurytus the Oechalian…”

and it continues: “…were led by the two sons of Asclepius, skilled healers, Podalirius and Machaon.”

Scholars widely agree that Tricca corresponds to modern-day Trikala. However, there is considerable debate regarding the locations of Ithome and especially Oechalia. Most researchers identify ancient Ithome with the current site bearing the same name, while others propose it was Aiginion, a fortified city in the Kalabaka region, though no archaeological evidence has confirmed this. As for Oechalia, scholarly opinion is even more divided — some associate it with Pelinnaion or Pelinna near present-day Petrotos in Trikala, others with Aiginion, and still others with Gomfoi itself. It is also quite possible that Homer’s references do not necessarily point to formally organized urban centers, but rather to broader geographic regions or clusters of villages whose names were later lost or altered over time.

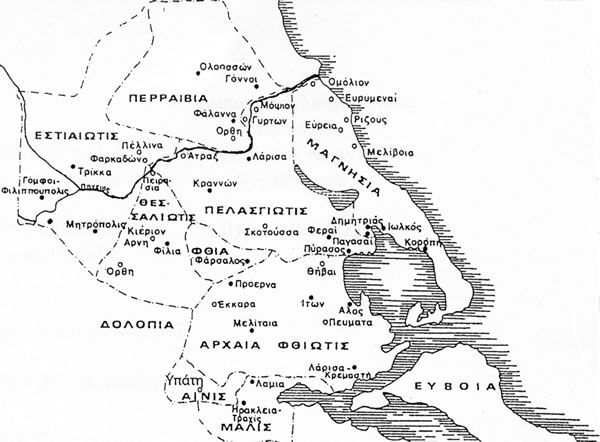

In the 8th century BC, the Thessalian tribe descended from Thesprotia, gradually occupying the whole of Thessaly. This movement forced the region’s earlier inhabitants to migrate further south, to the Boeotia of historical times. The earliest historical reference to the arrival of the Thessalians in Thessaly is provided by Herodotus. During the second half of the 6th century BC, the administrative organization of Thessaly was carried out by Aleuas the Red from Larissa, who divided the region into four sections (the ancient “moirai”), known as the “tetrads”: Pelasgiotis, Thessaliotis, Histiaiotis, and Phthiotis.

Indeed, this division remained in effect until the end of the history of the Thessalian League. The administration of the “tetrarchy” fell under the authority of a high-ranking official, who bore the title archon, archos, or tetrarch, while from the time of Jason of Pherae onward, the title tagos was used. Particularly characteristic are the words of Jason, as conveyed by Xenophon, that Thessaly is governed by a single tagos, “to whom all the surrounding nations are subject.”

The city of Gomfoi, built on the border between Istaiotida (or Estiaiotida) and Thessaliotida, belonged to the region of Estiaiotida, which, according to Strabo, owes its name to the inhabitants of Histiaea in Euboea, who were forced to relocate there when their city was taken by the Perrhaebi. Gomfoi was situated at the foot of Mount Itamos, in a valley formed by three hills—Vouloto, Palaiomonastiro 1, and Palaiomonastiro 2—as well as the riverbed of the Pamisos River, at the location now known as Episkopi, approximately 1.5 km northeast of the modern town of Mouzaki. The name of the city probably derives from the Greek word gomphos, which referred to a thick wooden or metal pin used to join separately constructed parts of temples or works of art. The comparison is particularly apt, as the city served as a link between Estiaiotida and Thessaliotida, as well as between Thessaly and Athamania and between Thessaly and Ambracia. According to Strabo, it belonged to the strategic quadrangle of fortified cities that included Trikka (modern Trikala), Mitropolis, Pelinnaion, and Gomfoi. In parallel, the Pamisos River is mentioned by Herodotus as one of the five major rivers of Thessaly. Pliny the Elder, in his Historia Naturalis, also refers to Gomfoi as one of the most important cities of Thessaly, alongside Pherae, Larisa, Thebes, Trikka, the city of Pagasae (later known as Demetrias), Pharsala, and Crannon.

The particularly strategic and timely location of Gomfoi led its inhabitants to build a strong fortification system for the city. There were two defensive walls. The outer wall, made of large poros or stone blocks, according to archaeologist Mr. Chatzhiangelakis, ran along the ridge of the hills from the southwest to the northeast and was reinforced at intervals with towers. The inner wall was constructed using raw mudbrick slabs covered with roof tiles. The main urban area of the city was located in the region known today as Episkopi and was surrounded by two satellite settlements: one at Palaiomonastiro and the other at Lygaria.

The inhabitants were primarily engaged in the cultivation of cereals, as well as viticulture, given the numerous references to the region’s exceptional wine. According to inscriptions that have been discovered, the city worshipped “Karpius” Dionysus, whose sanctuary is believed to have been located at the site of Agia Triada, between the villages of Gomfoi (Rapsista) and Lygaria.

In ancient Gomfoi, Zeus Akraios was also worshipped, with the epithet “Palamnios,” the punisher of those who had committed murder. According to Livy, along the road leading from Gomfoi to Argithea, there was a sanctuary dedicated to Zeus Akraios, which some scholars place near the village of Vatsounia. The worship of Zeus Akraios is also evidenced by the city’s coinage; on the obverse of a silver drachma (circa 340 BCE), the head of Hera or a nymph is depicted, while on the reverse, Zeus Akraios is shown seated on a rock.

In another version of the city’s coinage, the rock was replaced by a throne in bronze and silver issues from the early 3rd century BCE. Additionally, a votive stele found in the area depicts the god Apollo as a lyre-player. Finally, an inscription discovered in Gomfoi contains a prayer to Isis, Osiris, and Boubastis, representing the only known reference to the god Boubastis outside of Egypt and the only mention of the god Osiris in Thessaly. It is likely, however, that this inscription was brought to Gomfoi from elsewhere, as there is no other source or testimony indicating the worship of Egyptian deities in the region.

Immediately after the Persian Wars, the Thessalians became actively involved in the politics of southern Greece, achieving the peak of their political and military power in their long history. At the same time, however, rivalry developed among the cities of Pharsalos, Larisa, and Pherae for pan-Thessalian dominance. Ultimately, the tyrants of Pherae prevailed, with the leadership of Jason significantly strengthening the Thessalian League. However, under Alexander of Pherae, power was abused—even at the expense of other Thessalian cities—prompting many of them to seek assistance first from Pelopidas and the Thebans and later from Philip II of Macedon.

In 352 BC, the Macedonians and their Thessalian allies, led by Philip, were victorious at the Battle of Crocus Field and subjugated Pherae and, essentially, all of Thessaly. Philip II was appointed as lifelong Tagus (military and political leader) of Thessaly, along with his descendants. In 345 BC, Philip renamed the city of Gomphoi to Philippopolis (or Philippi) and reinforced its population with settlers, having recognized its strategically critical location.

The city reappears under its original name in 330 BC, six years after the assassination of Philip II at the theater of Aegae. In 230 BC (and not in 208 as is often mistakenly reported), Ancient Gomphoi joined the Aetolian League, as evidenced by an incomplete inscription found in Delphi listing the names of the League’s hieromnemones: “En Gomphois Theodoros of Petraios, Petraios Antigonos son of Antiochos.” Gomphoi’s participation in the Aetolian League was likely a consequence of the Demetrian War, which pitted the Kingdom of Macedonia—then under the Antigonid dynasty—against the two confederacies, the Achaean and the Aetolian Leagues, with the Aetolians ultimately gaining dominance over most of Thessaly.

It is not precisely known when Ancient Gomphoi withdrew from the Aetolian League. It likely occurred around 210 BC, when Philip V of Macedon descended into Thessaly, bringing much of the region back under Macedonian influence. In any case, by 200 BC, during the Second Macedonian War, as Titus Livius recounts, the Aetolians—together with their ally Amynander of the Athamanians—had seized Kerkineion on the shores of Lake Karla and present-day Domeniko. Amynander advised them to attack Gomphoi in order to control the access routes to Athamania and Ambracia, which implies that even before 200 BC Gomphoi had either become autonomous or aligned itself with Philip V. The Aetolians, however, disagreed with Amynander and set up camp at ancient Phaika, in the area of Palaio Monastiro, to gain direct access to the plain. There, they were taken by surprise by Philip V, and their army narrowly avoided complete destruction thanks to Amynander, who led them through the narrow mountain passes of Athamania back into Aetolia.

In 198 BC, following the defeat of Philip V by the Romans under Titus Quinctius Flamininus at the Battle of the Aous, Amynander of the Athamanians, after seizing ancient Phaika, launched an attack against Gomphoi, primarily using Roman troops. The siege lasted for several days, but once the siege ladders were set against the city’s walls, its inhabitants surrendered. According to Titus Livius, the fall of such a strong fortress as Gomphoi triggered alarm throughout Thessaly, and one after another, the Thessalian cities submitted to the Athamanians and Aetolians, who became masters of the entire region—even though it was the Romans who had won the battles.

The rule of the Athamanians over Gomphoi must have been rather loose, as according to Livy, after his defeat at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC—which marked the end of the Second Macedonian War and the victory of the Romans—Philip V took refuge in Gomphoi, where he gathered the survivors of the battle. Following the end of the Second Macedonian War, the cities of Thessaly regained their autonomy, with Philip V acting as a kind of overseer. As a result, the cities of Thessaly began electing Strategoi (generals) with annual terms instead of Tagoi (military leaders). In 179 BC, the year of Philip V’s death, the Strategos of Thessaly was, according to the Chronography of Eusebius, Phyrinos, son of Aristomenes from Gomphoi.

During the Aetolian War in 191 BC, Philip V remained loyal to his alliance with the Romans, as stipulated by the peace treaty of 197 BC. With his forces combined with those of the Roman Marcus Baebius Tamphilus, he recaptured all the Thessalian cities that had been conquered by the Athamanians, including the ancient city of Gomphoi. He went even further, conquering Athamania and installing garrisons in its four major cities.

In 189 BC, the Athamanians revolted and expelled the Macedonian garrisons from Heraclea (near present-day Skoulikaria), Theodoria (near modern Vourgareli), and Argithea (in the area now known as Ellinika, between Argithea and Therino). The only city that remained under Macedonian control was Athenaion, present-day Rodavgi. Philip V, leading 6,000 men, arrived at Gomphoi, where he left the majority of his force and continued with 2,000 soldiers to Athenaion. Realizing that the entire region was hostile toward the Macedonians, he returned to Gomphoi, and with his entire army, he marched back into Athamania, where he was defeated in battle near Argithea by the combined forces of the Athamanians and Aetolians.

Philip V retreated to the safety of Gomphoi, where he further reinforced its fortifications, while the Athamanians regained control of their territory.

In 171 BC, during the Third Macedonian War, the troops of Licinius Crassus entered Thessaly through Athamania and encamped at Gomphoi. According to Titus Livius (Livy), Crassus felt particularly relieved by the safety provided by the fortified city of Gomphoi, especially after the perilous passage of the Roman legions through the narrow passes of Athamania. From Gomphoi, the Roman legions set out for the Battle of Callinicus, where they were defeated by the King of Macedonia, Perseus. However, Perseus was subsequently defeated at the Battle of Pydna by the legions of Praetor Lucius Aemilius Paullus, a defeat that marked the end of the Macedonian Kingdom and, in effect, the beginning of Roman dominance in Greece—and especially in Thessaly.

During the Roman Civil War, Gaius Julius Caesar, as he himself informs us in his memoirs “Commentarii de Bello Civili” (On the Civil War), arrived in 48 BC at Gomphoi, which he describes as the first city of Thessaly when entering from Epirus. According to Caesar, the inhabitants of Gomphoi had previously sent envoys requesting a Roman garrison for the protection of their city, and in return they offered him access to their local springs.

However, Caesar’s defeat by Pompey at the Battle of Dyrrachium frightened the inhabitants, who shifted their allegiance to Pompey. Thus, the Thessalian general Androsthenes gathered all the men of the region, both free and enslaved, within the walls of Gomphoi, in order to resist Caesar’s advancing army. At the same time, he sent messages to both Pompey and Scipio, requesting reinforcements, assuring them of his complete confidence in the city’s defenses, as long as help arrived quickly, since the city could not withstand a prolonged siege. However, Scipio was still in Larissa, and Pompey had not even reached Thessaly yet.

Caesar prepared his forces for the siege, urging his soldiers to exert every effort to capture the city, not only because it was rich and full of goods, but also because its fall would instill fear in the rest of the Thessalian cities. Indeed, despite its strong fortifications, Gomphoi fell shortly before sunset, and Caesar handed the city over to be plundered by his troops. Caesar’s strategy proved entirely accurate, as the city of Metropolis, which had also closed its gates intending to resist, immediately surrendered upon learning the fate of Gomphoi and its inhabitants, and was treated with leniency.

Plutarch, in his Lives, informs us that when Caesar captured Gomphoi, he was not only able to resolve the food shortage faced by his troops, but also relieved them of an infectious disease that had been afflicting them—most likely caused by poor nutrition. During the plundering of the city, the soldiers found and consumed abundant wine, and according to Plutarch, they became so intoxicated that they continued their march toward Pharsalus in a state of drunkenness:

“When he captured Gomphoi, a Thessalian city, not only did he feed his army, but also, in an unexpected manner, relieved them of the disease. For they came upon an abundant supply of wine, and having drunk freely, then, engaging in revelries and behaving like Bacchantes along the road in their drunkenness, they sweated out and expelled the illness, their bodies having shifted into a different condition.”

Another perspective on the destruction of Gomphoi is given by Appian in the second book of his Roman Civil Wars. Like Plutarch, he provides details about the plundering of the city and the excessive consumption of wine by Caesar’s soldiers, noting that the Germans were the most ridiculous of all. Appian adds that if Pompey had had the prudence to pursue Caesar after the battle of Dyrrhachium and attack him after the fall of Gomphoi, he would have easily secured a victory. Appian also informs us about the fate of 21 prominent citizens of Gomphoi, likely the city’s magistrates, who committed suicide due to the disastrous and, as it turned out, mistaken choice of political alignment. Twenty of them were found lying lifeless on the floor of what appears to have been a medical chamber, their bodies forming a circle, with drinking cups scattered beside them, as if they had died in a drunken stupor. At the center of the circle, seated on a chair, was the body of the eldest among them, who had apparently distributed the poison to the others.

After the siege of Gomphoi by Caesar and the fall of the city, the sources fall silent. This silence may indicate that the city declined following its destruction or that interest in the area waned, as—being located in the heart of the Roman Empire—it lost its former strategic importance. The city of Gomphoi is later mentioned in the report of Pseudo-Epiphanius, within a 7th-century A.D. revision of an earlier version of the Notitiae Episcopatuum (the official registry of Metropolises, autocephalous archbishoprics, and bishoprics). This list had been originally compiled by Patriarch Epiphanius during the reign of Justinian, and was revised during the reign of Emperor Heraclius, leading to the mistaken belief that Gomphoi became a bishopric during the time of Emperor Heraclius.

In reality, Gomphoi had already been a bishopric as early as 530 A.D., and in fact, a bishop of Gomphoi is mentioned at the council of Pope Boniface II in 531 A.D. Gomphoi is also referenced in the monumental work On Buildings (De Aedificiis) by Procopius, which was certainly completed before 558 A.D. In this work, Procopius states that Emperor Justinian restored the walls of Demetrias, Metropolis, Gomphoi, and Trikke, thus making these cities secure. The last written reference we have at our disposal is that of Pseudo-Epiphanius, mentioned earlier, dating from the 7th century A.D.

The city of Gomphoi appears to have been destroyed and abandoned by its inhabitants around the year 1600, during the revolt led by the Metropolitan of Trikke, Dionysios the Philosopher—nicknamed Skilosophos (“Dog-Philosopher”) by his enemies. Its bishopric had already been merged earlier with the Metropolis of Fanari, a bishopric for which the English traveler William Martin Leake, writing in 1810, noted that he found no trace indicating the presence of a church or monastery in the area of Episkopi.